Advances in technology, in particular information communication technologies made possible by smartphones and the Internet, are shaping and facilitating trafficking and smuggling crimes and creating additional barriers to their detection and investigation. This part will consider how technologies can be harnessed to prevent, detect, intervene, and ultimately thwart these crimes. It will also note another crucial aspect to this use of technology; namely, how states, law enforcement agencies and private bodies collect, retain, and use information harvested during these investigation processes. These actions all raise potential concerns regarding the privacy of personal data (see Cybercrime Module 10 on Privacy and Data Protection for more information).

There is growing interest in finding ways to “exploit technology” to disrupt human trafficking and migrant smuggling networks. For example, law enforcement authorities use technology to identify traffickers and smugglers and data mining to identify suspicious transactions (Latonero, 2012, p. v; European Commission, 2016).Technology at borders is increasingly deployed. This influences ease of movement but also affords an opportunity to combat smuggling, provided border forces are sufficiently trained on the issues and enabled to identify indicators of smuggling. Technology can also facilitate the recording, storage, analysis, and exchange of information relating to identified victims of trafficking. Further, evidence that suspects have applied fake caller IDs or spyware can be used to rebut claims of innocent association and to prove criminal intent. Flight bookings and bank records of cash withdrawals abroad assist in proving transnational trafficking.

Other useful and often incriminating sources of digital evidence include:

- Phone data – the reliance of modern traffickers and smugglers on their smartphones means that a wealth of evidence is available on those devices if they can be accessed;

- Social media postings – images, video, contacts, associates, locations, and other information can be gleaned from social media accounts; and

- Digital footprints, including the browser history on personal computers and IP addresses.

The use of this digital evidence allows for far stronger cases to be constructed. It can also support the accounts of victims and witnesses when they give evidence. In the absence of victims or witnesses to give testimony, digital evidence can be used on its own by prosecutors and authorities to bring cases to court and secure convictions (see Module 4 on Introduction to Digital Forensics, Module 5 on Cybercrime Investigation and Module 6 on Practical Aspects of Cybercrime Investigations and Digital Forensics of the University Module Series on Cybercrime).

Digital evidence may be available from exhibits seized from smuggled migrants or victims of trafficking, or from suspects. Law enforcement investigations are conducted to identify, investigate, and obtain evidence that will ultimately lead to the prosecution of traffickers and the protection of victims. In relation to transnational organized crime this needs to be cooperative. For example, the United States FBI’s Operation Cross Country, which in 2017 was run for the 11 th time in cooperation with other countries (Canada, the United Kingdom, The Philippines, Thailand and Cambodia), conducted these operations activities offline (in, for example, bars, casinos and truck stops) and online, resulting in the arrest of 120 traffickers (FBI, 2017).

The concepts of investigation and deterrence converge when it comes to the virtual presence of law enforcement, often in the form of “catfish” profiles being created to snare organized criminals operating online. The use of fake profiles can allow digital evidence to be gathered as part of an investigation. They can also act as a deterrent: if a would-be trafficker fears that he/she may be communicating with a police officer he or she is less likely to take that risk. However, care has to be taken where individual jurisdictions prohibit entrapment or “sting” operations.

The main obstacle to investigations is the amount of time needed to conduct them and an inability to engage in criminal activity save for authorized “undercover” operations. Technology can be leveraged to reduce the amount of time it takes to identify perpetrators and victims, and proactively remove trafficking/smuggling content. For example, chatbots can be utilized to engage in conversations with thousands of online abusers at the same time. It should be noted that ethical approval for some research techniques can be difficult to obtain, which can affect investigative progress, especially where jurisdictions have no political will to cooperate.

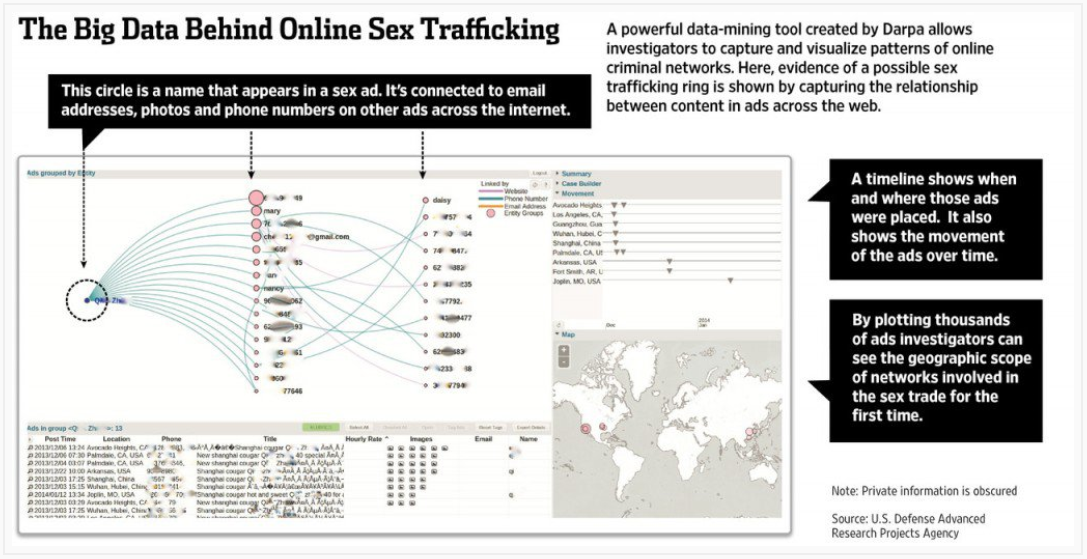

Another way to overcome investigative obstacles is through the use of web crawlers and data mining tools. The Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) developed tools under its Memex programme that have been used to identify human traffickers and trafficked victims. As part of Memex, web crawler and data mining tools have been developed that scrape online advertisements (on the visible and the deep web) and create databases with this information. In particular, these tools (such as DIG and TellFinder) comb advertisements, download content, identify links between downloaded items, add information databases, and enable database queries (Karaman, Chen, and Chang, n.d.; Pellerin, 2017). The information in these databases is mined to identify trends and patterns and these are mapped into visual formats. This mapping enables the identification of timelines and movements of victims (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Source: DeepDive website

Images

Images taken with mobile phones or digital cameras contain metadata (also see Cybercrime Module 4: Introduction to Digital Forensics). This metadata, known as Exif data, contains information about the camera used as well as the image itself, such as its dimensions and format. Exif data may match images to devices in the possession of a suspect. Similarly, Exif data may assist in providing the dates on which images were captured and crimes committed. The subject matter of images and geo-tagging can also be used to determine the location at which a material event took place.

GPS data

GPS data can be used for tracking location and device history. In one case from the United States in 2011, a man entered a guilty plea to trafficking offences after posting commercial services of a minor on Backpage. Investigators were able to use the GPS data on a trafficker’s car to establish the locations of several customers (Latonero, 2011). Another example of the use of satellite technology is the Geospatial Slavery Observatory project undertaken by Nottingham University, which uses geospatial intelligence to detect instances of slavery. In 2016 the Telegraph reported that this research had been used to uncover five previously unknown labour camps in Bangladesh which were suspected of using child slaves.

Private sector

Any efforts to harness technology to counter both smuggling of migrants and trafficking in persons inevitably involves cooperation between the private sector – developing software and sharing data and information – and law enforcement agencies and prosecuting bodies. In 2018, the Global Initiative against Transnational Crime announced the Tech Against Trafficking (TAT) initiative, a collaboration between global technology companies, civil society organizations and the United Nations to support the eradication of forced labour and human trafficking through the use of technology.

Examples of contributions from the private sector include Microsoft, which has organized academic fora in this area and developed a tool ( PhotoDNA) in 2009 to analyse images of child sexual abuse, which can be used (without charge) both by law enforcement agencies and businesses to locate and remove child sexual abuse images. Other companies have also developed software that identifies child trafficking victims through link analysis. For instance, Thorn’s Spotlight is used to identify online advertisements for sex with underage children by analysing vast quantities of data gleaned from online advertisements in order to identify patterns and connections (Thorn, undated). This tool has been used in undercover law enforcement operations, such as Operation Cross Country (Thorn, undated).

Banks can also play a role in the detection process. One avenue through which financial institutions are drawn into the fight against trafficking is the Liechtenstein Initiative, which encourages innovation in the financial sector to combat the crime. Although a full analysis of this Initiative, banking models and reporting requirements is outside the scope of this Module (see Economist article on software that detects human trafficking).

Social media

Anti-trafficking organizations use social media platforms, such as Facebook and Twitter, to communicate information about trafficking in persons and smuggling of migrants, post information about or links to trafficking and smuggling cases and relevant news stories, connect with other organizations with similar objectives, and post opportunities for civil society involvement in anti-trafficking and smuggling campaigns (Latonero, 2012).

These organizations also use video sharing platforms (such as YouTube) to educate the public about trafficking in persons and smuggling of migrants. For example, the Polaris Project – an NGO working to combat and prevent trafficking – uses social media and video sharing platforms to raise awareness, and also launched a texting service ( BeFree), available 24/7, where victims and survivors of human trafficking can receive assistance.

Reporting mechanisms for witnesses and victims via telephone or the Internet have been established. Another example is the joint initiative of the Bahrain Labour Market Regulatory Authority and the telecommunications company VIVA, which provides SIM cards to expat workers arriving in the country so that abuse can be reported.

Crowdsourcing

Crowdsourcing, “the act of taking a job traditionally performed by a designated agent (usually an employee) and outsourcing it to an undefined, generally large group of people in the form of an open call” (Howe, 2006), has been applied to anti-trafficking initiatives (Latonero, 2012, p. 20-21). One particularly innovative app, TraffickCam, invites members of the public to upload photographs of the hotel rooms they stay in, so that a crowdsourced database can be built with the images and the features of the rooms can be used to locate where trafficked victims are being held and/or abused. This identification is made possible by examining the surroundings of images or videos posted depicting the victim.

This is an area that will depend on trafficking awareness levels in a particular jurisdiction. As a lecturer, you can task your students to discuss current awareness levels in their countries and how awareness could be improved, if necessary.